|

|

- Introduction

- The sound of the serpent

- The serpent and the voice

- How does the serpent work

- Conclusion

- références

Etude acoustique sur le serpent et les voix, article publié lors du Congrès Européen d'Acoustique: Forum Acusticum 2005 qui s'est déroulé à Budapest du 29 Aout au 2 Septembre 2005 (Cette conférence a été donnée le 29 Aout 2005)

Vous pouvez choisir parmis les différentes rubriques de cette page:

|

|

Contribution of acoustic in playing early instruments in agreement with historical usage: the serpent as example.

Volny HOSTIOU

The serpent is a wind instrument, made of wood, played by means of

a mouthpiece, which classes it in the brass instruments family. Appearing

in France about the end of the XVIth century, the serpent was invented,

according to historical documents, to sustain voices in church choirs.

Imbert de Sens, who wrote the first method for serpent in 1780, gave

a predominant place to the serpent: « Cet instrument, dont l’utilité

pour l’Office divin, le rend au-dessus de tous les autres, est

établi pour soutenir les voix, les rendre juste… »

, This instrument, whose use in sacred music makes it the most important,

has to sustain voices and control the pitch of the choir.

Today, the serpent has been used again for the last 20 years in early

music ensembles. The musicians have to find the way to play serpent,

in agreement with historical usage. Acoustical studies are a means to

understand the interferences between instruments and voices in early

music formations.

Emile Leipp and Murray Campbell have pointed out acoustic characteristics

of the serpent for serpent players who have to search each note with

their lips to find the good intonation. We have completed these studies

by spectrographic measures realised with Charles Besnainou (Laboratoire

d’Acoustique Musicale de Paris, CNRS). This study shows especially

how the serpent completes the spectra of voices.

1 Introduction

Figure 1 : Baudoin (facteur), Serpent, France, XIXe siècle,

Paris, Musée de la

Musique, E. 575 (photograph, V. Hostiou).

The serpent is a bass wind instrument played by means of a mouthpiece.

It therefore belongs to the brass instrument family, even though it

is made of wood covered in leather. Its mouthpiece is similar to present

day brass instruments, close to that used for the trombone. We can also

compare it to that of the bass cornet, but its opening is wider.

In his Memoirs on the ecclesiastical and civilian history of Auxerre

[1], the only known document suggesting a precise date for the invention

of the serpent, Abbot Lebeuf attributes its creation to Edmé

Guillaume, a Canon from Auxerre. The date: 1590. Unfortunately, the

author does not give a source. With the absence of any precise documentation,

the exact origin of the serpent remains difficult to specify but in

the seventeenth century it developed all over France and became the

major instrument used to accompany church singing throughout the kingdom.

The serpent would appear to have been conceived as an accompaniment to choral singing, intensifying the bass line during services. At first it was essentially devoted to religious vocal music. It was to remain one of the leading church instruments until the middle of the nineteenth century, when, little by little, it was replaced by other instruments.

From the eighteenth century, as well as its religious function, the serpent had a very different use in military bands. It was to become one of the major instruments in these bands, which are closely related to present day wind bands. This new function led to a technical evolution of the instrument. Its shape changed to enable it to be more easily held and played while marching or riding on a horse. Extra keys were added for better intonation and greater virtuosity. A great many pieces were written for the serpent as a military instrument.

During the nineteenth century the serpent was also used in symphony orchestras. This new employment was often linked to the strongly charged religious symbol of the instrument itself: Mendelssohn devotes a part to it in his oratorio, Paulus and Berlioz features it in the Dies Irae¹ of the Symphonie Fantastique.

After gradually falling into disuse from the middle of the nineteenth century, the serpent was rediscovered in England by Christopher Monk, and he was the first to make serpents from a model belonging to French instrument maker, Baudoin.[2]

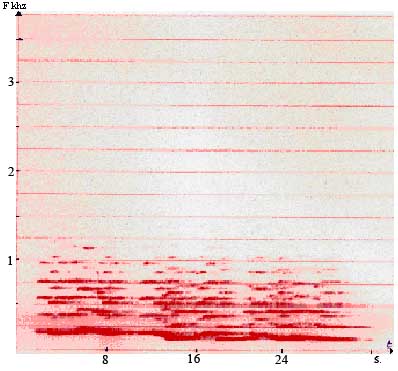

2 The sound of the serpent

The serpent is very close in conception to the bass cornet (an instrument made of wood covered in leather, played by means of a mouthpiece). They have the same spectrographic signature: five main successive harmonics.

Figure 2: Spectrogram of the serpent on ut 2 (serpent player : V. Hostiou)

However, the serpent has its own distinctive sound, due to its wide

opening and mouthpiece, shaped like a spherical bowl. In contrast to

the bass cornet, which has a direct, dense sound, and modern brass instruments,

which have a bright, showy sound, the serpent is a very soft instrument,

with a warm sound that fills the space around it. These characteristics

are ideal for the precise use to which it was put: the accompaniment

to church choirs.

The choice of mouthpiece is very important for the quality of sound.

We have carried out a study on the important collection of mouthpieces

in the Musée de la Musique in Paris. [2] There are two types

of bowl shape for serpent mouthpieces. The first is a conical shape,

which gives a very bright sound with a lot of interference's. We suggest

that this was the most effective sound for serpents used in military

bands but it is not the best sound we can obtain with a serpent.

The other mouthpiece shape, used on older instruments, is a hemisphere. With this, we can produce a very large and pure sound, close to that of the human voice, which fits in with the serpent¹s historical role as accompanying instrument to a church choir.

Figure 3 and 4: Serpent mouthpiece and X-ray photography (spheric bowl)

X-ray photo, Musée de la Musique de Paris

3 The serpent and the voice

Treatises and writings about the serpent in the seventeenth and eighteenth

centuries clearly indicate that this instrument¹s purpose is to

accompany voices. Abbé Lebeuf, who provides the earliest evidence

of the serpent, shows it clearly in his text on Edmé Guillaume

(creator of the instrument according to Lebeuf): «[Edmé

Guillaume] invented an instrument capable of giving a new quality to

Gregorian chant. »[1]

Therefore the sound of the serpent has to merge with the voices and support them without drowning them. Mersenne praises the quality of the serpent¹s sound in his Universal Harmony:

« Or cet instrument est capable de soustenir vingt voix des plus fortes, dont il est si aysé de ioüer qu’un enfant de quinze ans en peut sonner aussi fort cômme un homme de trente ans. Et l’on peut tellement en adoucir le son qu’il sera propre pour ioindre aux voix de la musique douce des chambres, […] » [3]

Now this instrument is capable of supporting twenty of the strongest voices, and is so easy to play that a young person of fifteen can produce as strong a sound as a man of thirty. But its sound can be softened to make it suitable as an accompaniment to quieter chamber music choirs.

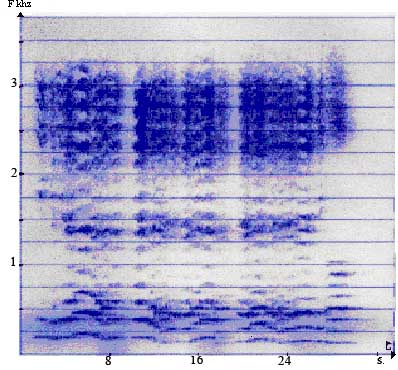

As far as the characteristics of the sound of the serpent are concerned, a spectrographic study by Emile Leipp shows that the voice and the serpent are complementary. Indeed the instrument reinforces the deep harmonic spectrum of the voice.

« Pourquoi Mersenne et d'autres, insistent-ils sur le fait que le serpent est surtout utile pour accompagner les voix, les soutenir dans le grave, leur « donner du creux » (entendez du fondamental objectif.... ). Pour comprendre à quel point ces observations et cet usage sont justifiés, il suffit de comparer l'allure de spectre du serpent avec celle d'une voix de basse d'opéra .... Ici, le chanteur produit des spectres denses dans la zone sensible de l'oreille; il "place" sa voix pour la rendre auditivement la plus efficace possible pour l'oreille; mais le "grave" du spectre d'une voix de basse ne montre que peu d'énergie dans les fréquences graves : le serpent apportera donc du « creux » dans l'association serpent-chanteur. » [4]

Why do Mersenne and others stress the fact that the serpent is especially

useful for accompanying voices, supporting them in the low register,

and filling in the gap. To understand why these observations are in

every way justified, one only has to compare the spectrum of a serpent

with that of an opera bass. Here, the singer produces dense spectrums

in the sensitive are of the ear: he projects his voice so that it can

most efficiently heard. But the bass singer¹s spectrum shows that

there is little energy in the deeper frequencies: so the serpent will

complete the deep register in the serpent-singer combination.

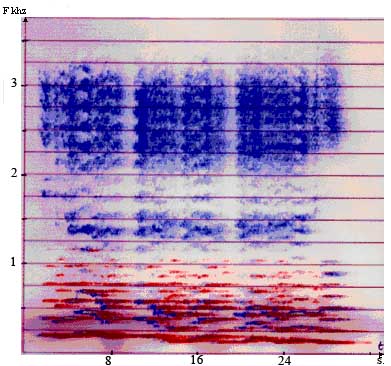

The following spectrograms, show the complementary nature of the serpent

and the singers in the deep harmonic spectrum: recording of a Kyrie

in plain song (3 bass singers with one serpent)

1: Serpent alone

2 : Singers alone

3 : Singers and serpent together

In blue: the singers’ spectrum, in red the serpent. Measurements

carried out by Charles Besnainou in Pontigny Abbey with three basses

and a serpent. (V. Hostiou)

Figures 5-8, spectrographs: serpent and voices sounds

4 How does the serpent work

Another characteristic of the quality of sound produced by this instrument is the importance of resonance. The serpent produces a a direct, rather thin sound as it leaves the body of the instrument, so wind and interference are audible. It is the ambient acoustic, if it offers sufficient reverberation, that allows the development of the serpent¹s sound. It can fill the space, even if it is very large, without emitting a too powerful direct sound. When accompanying a choir, the serpent fill out the harmonic bass by reinforcing the bass voices.

The position of the six holes on the serpent in the seventeenth and eighteenth century, before the keys were added, does not have any logical, acoustic reason, and that is why the serpent player must regulate the intonation for every note by adjusting air pressure and lip position. If the player constrains the sound too much with his lips, the resonance of the serpent, which gives the sound its colour, will not be used. In consequence he must adjust his playing to focus the sound of the serpent, and find its resonance in order to best fill the space in which he is playing.

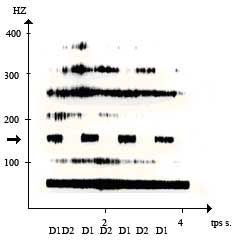

The purpose of the holes is essentially to favour certain harmonics and not to determine a precise note. [5] The following diagram show the difference in the spectrum with two different fingerings for the same note, at exactly the same pitch.

Figure 9: This spectrograph shows two fingers combinations for a same note

We can see clearly that the third harmonic component is present or not according to the fingering D1 or D2. Measurements by Charles Besnainou in L.A.M., serpent : Volny Hostiou

5 Conclusion

The serpent, played ideally in a church type acoustic, forms a warm bass enveloping the sound of the voices without supplanting them. When a serpent accompanies a choir, it widens the harmonic base considerably by reinforcing the basses and causing them to resonate.

If an acoustic study does not permit sufficient insight into the workings of the serpent to allow the design of a perfect instrument, it does however, illustrate the musician's perspective and corroborates the existing historical documentation.

[1 ] Jean Lebeuf (abbot), Mémoires civiles et ecclésiastiques

d’Auxerre, Paris, Durand, 1745, Vol.1, p.643.

[2] You can find more historic and musical details about the serpent

in the book of the same author : HOSTIOU, Volny, Le Serpent d’église

en France de son apparition à la Révolution, Master of

musicology conducted by F. Billiet, Paris 4 Sorbonne University, may

2004, 171p.

[3] Marin Mersenne, Harmonie Universelle, Paris, 1636, reprint, C.N.R.S., Paris, 1986, vol 3, livre 5, proposition XXV, p. 281.

[4] Émile Leipp, « Le serpent un monstre acoustique », Bulletin du Groupe d’Acoustique Musicale, n° 63, Oct 1972, p.11. (the author didn’t reproduce the ? which enable him to end up these conclusions).

[5]Murray Campbell, « Intonation et résonances acoustiques des cornets à bouquin et des serpents », Acoustique et instruments anciens, colloque organisé par la Société française d'acoustique et la cité de la Musique, 17 et 18 novembre 1998, Cité de la musique, Société française d'acoustique, 1999, p. 125-137.